Why your Black friends cancelled Liam Neeson

Actor Liam Neeson spoke to Britain’s Independent newspaper this week while promoting another one of his “old guy on a rampage avenging a loved one who was wronged in some way with guns and stuff” epics we have all come to love ever since Taken became a meme.

You know the meme I’m talking about; it’s so ubiquitous that hardly anybody can look at a picture of Neeson holding a cell phone without reading whatever is written in that calm, gravelly voice he used in the movie.

Here. Let’s do it together.

Between the typically banal movie promo drivel that characterizes most junket interviews, Neeson tells the story of a time when his friend was apparently raped by a Black man, and then casually lets slip this insanely racist nugget:

“I went up and down areas with a cosh [wooden bat/club], hoping I’d be approached by somebody – I’m ashamed to say that – and I did it for maybe a week, hoping some – [Neeson gestures air quotes with his fingers] – ‘black bastard’ would come out of a pub and have a go at me about something, you know? So that I could – [another pause] – kill him.”

You can read the full interview here.

The response to this insanity was predictably split mainly along racial lines, with myself and the majority of Black people that I know immediately cancelling Liam Neeson.

To be super clear, I/we did not call for his movie to be cancelled, or for him to be kicked out of showbiz (whatever that means). What this means is we personally cancelled him: we will no longer be supporting his projects.

Sadly – based on the social media and in-person conversations I’ve had since this story broke – many of my white friends don’t understand this cancellation. The calls to show empathy and patience were almost immediate, with some people making the argument that this was many years ago, and that if we were to cancel everyone who “made a mistake,” everyone would be cancelled…

First off, no. Sorry but no. I know many people who have lived a life without doing something so egregious that I think they deserve immediate cancellation. It’s really not that hard. Furthermore, I’m not sure people understand: Liam Neeson is not cancelled for what he thought; he is cancelled for what he did.

We all have moments of weakness when our lizard brain takes over and we indulge in dark fantasies that feed our desire for instant gratification. That is not what Liam Neeson did. He said he walked the streets, armed with a bat, for several nights, looking to “kill some black bastard.” That is not a mistake. That is textbook racism.

Sadly, I, like many other men, have many female friends who have been raped or sexually assaulted – and movements like #MeToo and #TimesUp have made me realize how pervasive the problem of sexual assault is.

When my friends have shared their experiences with me, at no point did I inquire as to the race of their assailant. I also didn’t have an impulse to arm myself and roam the streets looking for any random person who shared the race of my friend’s attacker so that I could kill them.

If you do have thoughts like these, I’m sorry to inform you that you are a racist. It’s a hard thing to hear, I know, but it’s true. This is not a normal thought to have. It is no more normal to want to kill any “black bastard” because your friend was allegedly raped by a Black man than it is for some incel to shoot up a yoga studio full of women because girls in his immediate area won’t date him.

Taking your hatred or anger intended for one individual and then directing it onto a larger group that the individual is tangentially related to is irrational bigotry. Period.

What makes Neeson’s actions worse is right there in the history books. There’s a well-documented history of Black men being lynched, castrated, shot, tortured, and slaughtered under false pretences, often for being suspected of making unwanted sexual advances towards white women. This has been going on since the days of slave plantations. The myth of Black men as hyper-sexualized predators lusting after and out to harm innocent white women is as old as the United States and Canada.

This myth was famously depicted in D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, which presented the KKK – yes, that KKK – as heroes protecting white women from savage Black rapists.

This myth was at the root of Emmett Till’s horrific murder in 1955. Till was accused of flirting with and making inappropriate gestures towards a white woman at the height of America’s Jim Crow era. As a result of these accusations, Till was kidnapped from his uncle’s home by armed men, tortured, mutilated, shot in the head, and then dropped in the Tallahatchie River. Decades later, his accuser – a white woman named Carolyn Bryant Donham – admitted that she’d fabricated most of her story.

Emmett Till and his mother. Image via Wikipedia Commons.

[To view graphic post-mortem photos of Emmett Till – photos that many historians have described as sparking the Civil Rights movement, and were published in newspapers at the request of Emmett Till’s mother – click here. Discretion is advised. –Ed.]

There are also examples of this today. Last October, a woman named Teresa Klein accused a young Black boy of touching her behind in a Brooklyn bodega and demanded the police be called. Video footage later revealed that she’d lied.

Black men die because of white people’s lies on a regular basis.

One of our worst fears is that we are assaulted or killed by some angry white man in a case of mistaken identity – or, worse still, that someone like Liam Neeson, enraged at our entire race for reasons that have nothing to do with us, will seek retribution for crimes we had nothing to do with. This is a fear that Black men keep buried in our subconscious every minute of every day, because history has shown us that this could not only happen, but that our assailant will likely get away with it.

So when we tell you Liam Neeson is cancelled, don’t debate us. Don’t play devil’s advocate. Understand where we are coming from – and then kindly shut your mouth and take several seats.

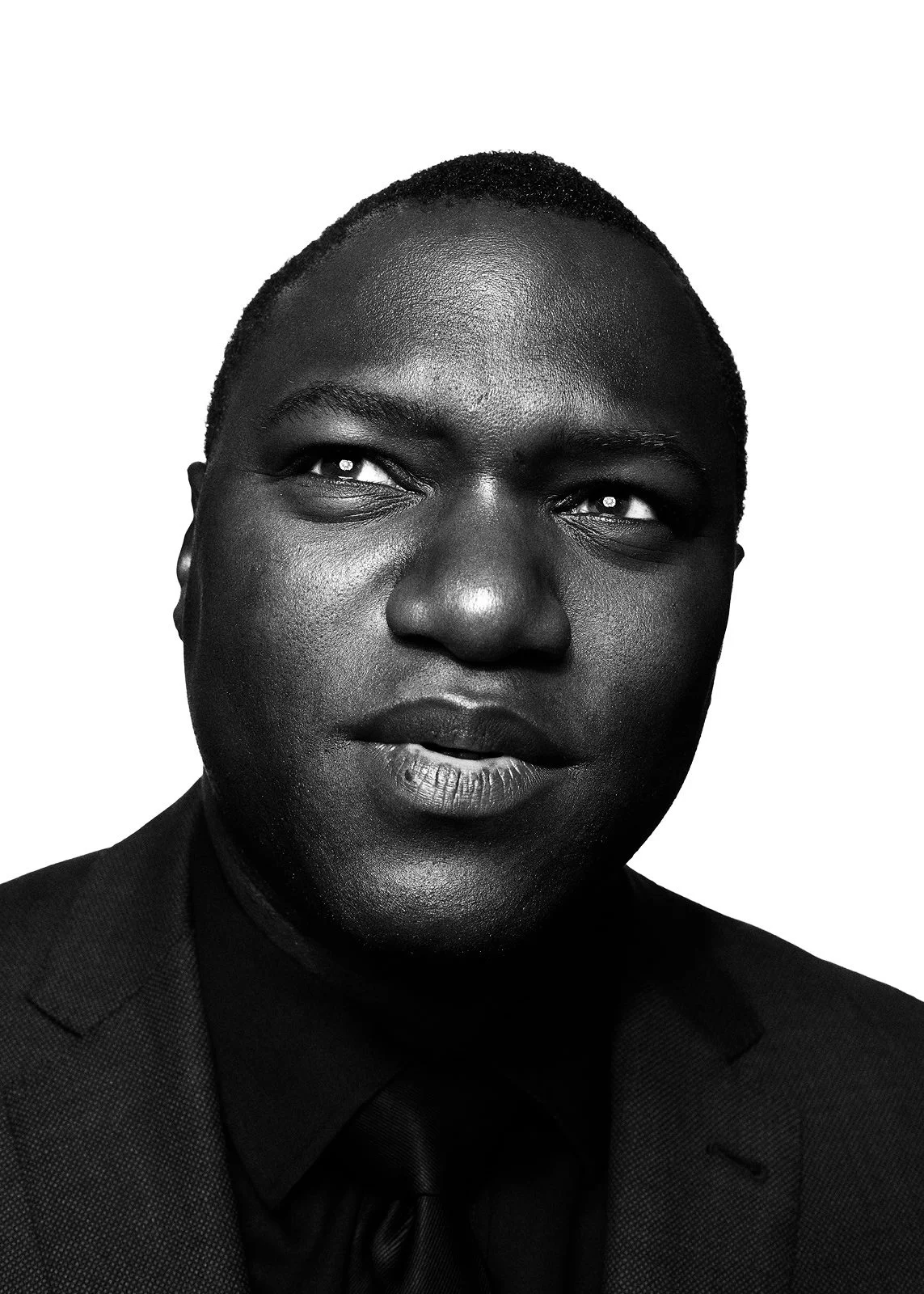

Editor’s note: Omari Newton is a creative force who has made a mark in multiple cities across Canada: in Montreal, where at 19 years old he won accolades for his performance in Athol Fugard’s ‘My Children! My Africa!’ with Black Theatre Workshop, Canada’s oldest Black theatre company; in Ottawa, where his play ‘Sal Capone’ will run in the second half of the National Arts Centre’s 2017-2018 season; and in Vancouver, where he’s straddled the screen and theatre worlds as an in-demand actor (‘Continuum’), producer (‘The Shipment’), playwright (‘Sal Capone’), and teacher. Omari won a 2018 Jessie Award for his performance in ‘The Shipment.’ Social justice issues are important to Omari – he writes about them on his Facebook page, Visible Minority Report – and are central to his work in the arts. Omari writes about social justice issues – and how they intersect with the entertainment industry – for YVR Screen Scene. Omari directed a production of David Harrower’s ‘Blackbird’ that ran at the 2018 Vancouver Fringe Festival.